I love history. Maybe that is one of the reasons I enjoy returning to the UK so often - visiting new places there is almost always inextricably intertwined with a walk back in time. In this post, allow me to teleport you to the late 1700s. The Industrial Revolution started in the middle of the century, bringing new machinery that saved time and made some people very wealthy. By contrast, it was a difficult life for poor people.

A rising population, rural unemployment and migration to towns were the hallmarks of this period. I am reminded of the Opening Ceremony for the 2012 Summer Olympics, which took place in London. The most-viewed Olympic opening ceremony in the UK and the US, it featured vibrant storytelling. I can still see the farm fields being stripped away to reveal the rising mills and factories of the industrial era. Remnants of this epoch can be seen the length of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. On November 2, 2021, we walked just 6 miles of it!

We began near Keighley, just across the road from East Riddlesden Hall (see December 19, 2021 post). I was immediately entranced with the curves of the canal, the autumn leaves scattered along the path, the mirror of the water reflecting the trees back to the sky, itself populated with fluffy clouds. Canals were the equivalent of our motorways, with the boats like lorries (read: trucks) transporting freight. In the early days of canals, the boats were pulled by horses. Their legacy? Scenic, smooth, flat walking trails!

This particular canal runs 127 miles from Liverpool in the south to Leeds in the north. We walked south-bound, and the periodic mile markers (just like a highway!) reminded us how far we had come.

Birds were prolific along the path, but difficult for me to photograph. Imagine my delight when several swans paddled to us, along with their cygnets! Check out the video!

Some stretches of the canal were wild and untamed; others were lined with houses. It appeared to me that some industrial properties had been converted into apartments. Would you like to live in a 18th century building along a scenic canal?

Staircase locks were used by early canal engineers to overcome sudden changes in height. They are very wasteful of water and in later periods, engineers chose more sophisticated options such as inclined planes and boat lifts.

The Five Rise Locks (to the left) and Three Rise Locks (1.5 miles further south) were built in 1774. Both were designed by John Longbotham of Halifax, the Canal's first engineer.

As luck would have it, a canal boat arrived at the base of Five Rise Locks just as we did. Over the next 20 minutes, we watched the lock-keepers open and close the gates, allowing the boat to rise 60 feet and continue on its way north. Below are two videos; the first one is five minutes and shows the boat entering the first lock. The second video is one minute; the boat is guided into the final lock. Fascinating stuff!

At this site, signs explained the lock mechanisms and provided maps of the walking trails and other points of interest.

Bingley prospered during the Industrial Revolution. Several woollen mills were built and people migrated from the surrounding countryside to work in them. Many came from further afield such as Ireland in the wake of the Irish Potato Famine. The chimney stack you see in the photo to the right gives testimony to the mills of that day. (This is the same stack you see in the first photo of this post.)

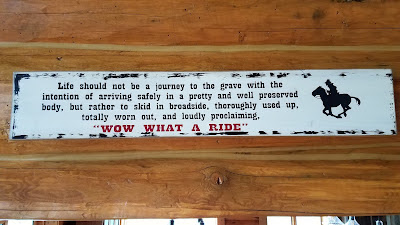

We paused at a pub for a refreshing beverage, and I was quite amused by the sign. "Beer shortage coming soon ... panic buy here!!!" That's one way to turn the downsides of the pandemic into some humor and good old-fashioned marketing!

In the 19th century, Sir Titus Salt chose to build his textile mills and a village for his workers here. With the village, Sir Salt's intent was to create a model community where his workers would be healthy and contented and fine fabrics would be produced in his modern and efficient mill. Quite a progressive idea for its time!

Work began on this beautiful church in 1856, and it was opened/dedicated in 1859. Sir Titus Salt paid 16,000 pounds for the building; in today's money, that would be $2.6 million! The Salt family is interred in a mausoleum on the south side of the church.

To become a World Heritage Site, Saltaire had to demonstrate that it had "outstanding universal value". Saltaire is a complete and well-preserved individual village of the second half of the nineteenth century. Its textile mills, public buildings and workers' housing are built in a harmonious style of high architectural standards and the urban plan survives intact.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)